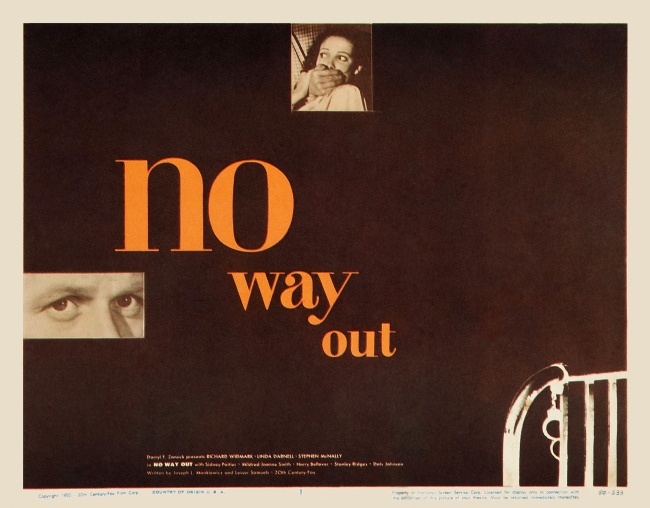

No Way Out (1950, Joseph L. Mankiewicz) is an unsubtle parable of age-old class and race tensions. But it’s executed so energetically and directly that it feels fresh and urgent. We sometimes assume that an old movie is no more germane to our modern lives than a manual typewriter. Quaint and intriguing maybe, but not very relevant. But as No Way Out reminds us, technological progress comes at a far faster rate than ideological. The movie’s cars and radios may be out of date, but the social forces that propel the characters are totally our own: disenfranchisement, class resentment, race-baiting, sexual threat, explosive violence. And the performances are first-rate: Sidney Poitier, Linda Darnell and Richard Widmark are gorgeous and totally human, absolutely recognizable as our neighbors and our selves.

Here’s the layout: Sidney Poitier is a young black doctor, anxious to prove his worth in the mostly white, mostly patrician medical establishment. Two white brothers, wounded while committing a robbery, are brought to his care. When one of them dies, Poitier is faced with trying to absolve himself of a murder accusation lobbed by the resentful survivor (Richard Widmark). While this is a transparent set-up for exploring race tensions, the story that unfolds feels genuine and unpredictable. And the performances are sharp and stirring.

A very young Poitier plays his role with great solemnity and self-control. Given that the film was made in 1951, it’s hard not to imagine some similarity between Poitier’s position as an actor and that of the young doctor he plays. Both have to prove themselves in a hostile climate. Though the Poitier character is never officially accused of wrongdoing, or even crummy doctoring, he spends the film defending himself against Widmark’s sleazy accusations anyway. He says he wants to prove to himself that he wasn’t careless or vengeful in treating an antagonistic white patient. But beyond this, it’s obvious how precarious his position is– hospital employees are already nervous about a young black doctor, already reluctant to take him seriously as an authority- so unless he can prove himself more honorable, more immaculate than the average intern, he may risk losing all he’s worked for. Further, he can sense creeping doubt in his white mentor (Steven McNally), the older doctor who has believed in him, and helped make a place for him in the hospital. The older doctor is a crucial ally he can’t afford to lose. Most urgently of all, he needs to clear suspicion in order to protect himself and his community from potential white vengeance.

Played with zeal by blonde, creepily boyish Richard Widmark, the dead man’s brother is the film’s antagonist. Intent on blaming Poitier for the death of his brother, Widmark refuses to admit that illness was responsible. He prohibits an autopsy. But it’s obvious that, though grieving, Widmark’s resentment of Poitier isn’t really about a man’s death. What’s really got him furious is the humiliating dead-end of his own life. First a thwarted robbery and major injuries, next he’s on his way to prison. Finally, upon entering the hospital, he finds a black man in charge of him. For this failed, bitter white guy, Poitier’s higher status is a withering reminder that he’s got no one left to feel superior to. And he can’t accept it. He uses every trick at his disposal to terrorize Poitier, to prove to himself that he’s still some kind of top dog .

Part of what makes No Way Out so effective is that Widmark isn’t a cartoon villain. He’s got human reasons. We know where his anger comes from. We don’t really sympathize with him, but we do get him. Without overdoing it, the movie lets us know that Widmark’s had a harsh life, that he’s swallowed plenty of degradation and been sneered at by those with creature comforts and influence. Feeling a cut above another disparaged group is his one paltry comfort. A comfort that seems ever more urgent as his failures and losses pile up.

The story is pretty compelling already, but when Linda Darnell enters the picture, it gains its most nuanced human trajectory. Where Widmark is ruthless and Poitier has to be impeccable, Linda Darnell is torn-up and uncertain. She enters the film when Poitier and McNally track her down in a shoddy, cramped apartment. She’s the ex-wife of the dead man. The doctors hope she’ll override Widmark and grant them the autopsy. But when they find out she’s divorces, they have to try another tack. They ask her to talk to her ex-brother-in-law, to try to make him see reason. But she doesn’t know or trust these men, so she’s not eager to help.

Darnell’s performance is really good. She’s carries herself with honest fatigue; her usually sultry beauty here just heavy and sullen, as if beauty is one of many old burdens she’d like to shed. You don’t have any trouble believing that she and Widmark grew up in the same grimy place because they’re both equally bitter, equally disgusted with the world. But unlike Widmark, Darnell isn’t totally unreachable. McNally begins to win her sympathy when he mentions the roughness of the old neighborhood, Beaver Canal, that she shared with her ex-husband and Widmark. McNally talks down Beaver Canal and talks Darnell up, reminding her how far she’s come. And you finally hear some hope in her voice. She did get out of Beaver Canal and she’s proud. It was an ugly place and she wanted something better. But despite her shift in mood, she’s not fully on Poitier’s side yet.

Like everybody, Darnell has family ties, community loyalties, old feelings. So she wants to hear Widmark’s side of things. She gets dressed up (that fulsome Darnell beauty suddenly apparent again) and uses McNally’s business card to talk her way into visiting Widmark at the prison hospital. In a short scene with a prison guard, Darnell’s toughness and resourcefulness are established. It takes just a few moments–a bit of flirting, a subtle threat–and then she’s in the infirmary, alone with Widmark.

You can see there’s plenty of tense history between them. It isn’t thoroughly explored, but multiple layers are hinted at- guilt, desire, resentment, fear. She guards herself, reluctant to get to close and tries to ask some questions. She wants to know his side of the story; maybe she also wants to help the doctors. But Widmark’s agenda is set, he isn’t going to let her in: he just wants to hurt Poitier. As they talk, he observes her guarded but obvious respect for the two doctors, and works swiftly to change her tune. He wastes no time reminding her who she is, reminding her that wealthy doctors can’t be trusted, reminding her of a lifetime of being nobody. And just like that, she’s angry. It’s not hard to stir up old class antagonism.

Darnell’s resentment feels so natural and earned, we get why she listens to Widmark. And we see again, this time filtered through a character far more sympathetic than Widmark’s, how fierce resentment can be for someone who grows up belittled, poor and shoved aside. She’s afraid of being used by the same people who’ve made her feel small all her life. So she’s not gonna give them the chance. It’s that ancient, ugly, human instinct: better to hurt than be hurt.

Soon she’s back in Beaver Canal, delivering Widmark’s lies and distortions, stirring up self-satisfied community rage against a black man. But thanks to the boys of the old neighborhood, her allegiance to Widmark doesn’t last long. These guys are a grim lot, sadistic and spiteful. Even more blatantly that Widmark, they treat Darnell as a pawn in some ugly game. Though she came solely to deliver a message, they insist she participate in the racial terrorism they’re planning. Further they’ve got unwelcome sexual demands. It doesn’t take her long to decide she wants no part of them.

But Darnell is really trapped. Though she tells them she needs to get to work, that she has a restaurant shift, they tell her that’s too bad ’cause she’s staying. Using both threats and force, the boys make her another target of their torture. They’re revved up and she’s a plaything.

But Darnell is a smart cookie. She isn’t about to give up. It takes time, luck and real resourcefulness, but she maneuvers out of their clutches. There’s wonderfully tense scene where she uses the heightened volume of a radio as a strategic cry for help. It’s exciting to watch such determined resourcefulness, to see this thoughtful heroine transforming everyday objects into tools for survival. She eventually uses similar strategies to help Poitier too. Because after her visit to Beaver Canal, she begins to figure out that she and Poitier are in the same boat. Because they want the same thing- a way out of this quagmire of poverty, hatred, and domination.

Darnell’s journey is one of the film’s great strengths. She’s a complicated female character. Tough, clever, jaded, defensive. Beautiful too, but she isn’t saddled with the standard motivations that movies usually give stunning women: she’s not seeking romance or a pot of gold. Instead she wrestles with group loyalty, self-preservation and urgent, intimate questions of right and wrong. Thoughtful and brave, she not only ends up not only fighting for herself, but eventually teaming up.

I won’t tell the rest of the story here, but it’s never less than gripping. The characters and performances are passionate, crafty, and brave. The various settings—bleak hospital ward, sinister junkyard, squalid apartment– are authentic and meaningful. But perhaps most impressive is the film’s feminist, populist heart. Not only does the film offer a realistic portrayal of the financial desperation and class resentment that often underlie racial antagonism, but the movie makes a tough, bright working-class woman its struggling hero. No Way Out isn’t a perfect film. It’s occasionally pedantic and preachy. But it mostly isn’t. Mostly, it just shows you what people are up against.