This post is part of the Classic Movie History Project Blogathon. Be sure to check out other entries here, and here, and here!

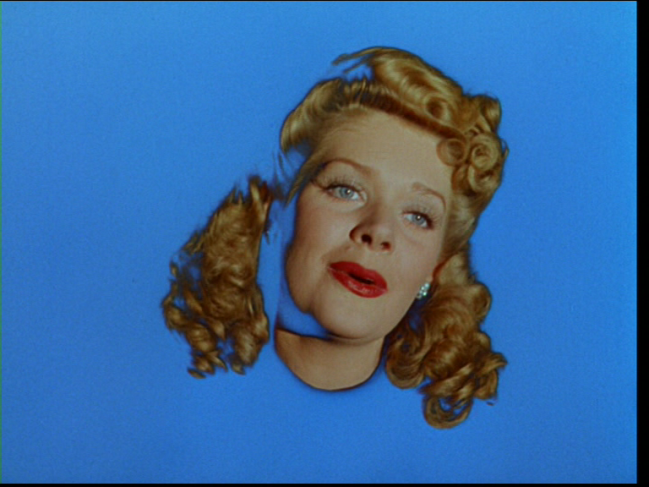

Despite a fair obsession with old Hollywood, I’ve ignored Loretta Young for most of my movie-watching life. I just didn’t think she mattered. Her movies don’t tend to end up on must-see lists. And more persuasively, (for me) she’s not celebrated as an aggressively tough or aggressively sexy figure, nothing fiery that could have made her a lasting icon. But after happening on some of her startlingly great pre-codes, I got interested. In her 1930s films, Young is phenomenal— tough, sensual, smart. That got me wondering what else I missed. And why nobody talks about Loretta Young anymore.

So I investigated. (Well, I read a bunch of stuff…)

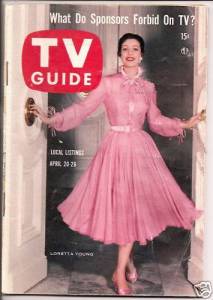

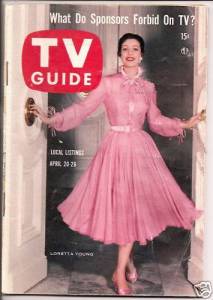

Loretta Young had an extraordinarily long and successful Hollywood career. She began in silents, then carved out a stunning “talkie” career that took her through the wild pre-code 30s, the more elegant 40s, and on into the wholesome 50s where she was a major television figure for 11 more years (The Loretta Young Show). Hard to beat. But despite all her glamour, talent, and longevity, her name and image aren’t in the pantheon. She’s not remembered like Garbo, or Bette Davis. Or even Ava Gardner.

In The Star Machine, Janine Basinger reasons that this is in large part because in the 50s Young’s image became that of the ultimate lady. In her television show, Young presented herself as a grand dame, elegantly sweeping through a door and into America’s living room—the impeccable1950s hostess, smooth, refined and perfectly garbed. Even if her actual weekly roles varied in type and wholesomeness, they were always framed by Loretta playing Loretta, fluid and decorous, introducing her weekly teleplay. Not the kind of image that suits our modern fancy for the overtly sexy, or the fallibly neurotic. Furthermore, Young was openly religious, unafraid to claim her Catholicism as essential to her identity. In other words, she seems like a bore. An entitled square. No one (excepting perhaps Meryl Streep ) makes a career out of being a lady anymore. Hipness and edginess are nearly essential components to modern-day stardom. Or to reclamation and rediscovery. So it’s unlikely Young ‘s image will experience a major revival anytime soon. These days even fictional “ladies” are roundly dismissed or despised (Betty Draper, Sansa Stark)— they seem cold and shallow or wimpy and victimized. Which is not entirely fair, given that holding it together and acting the lady was not only supremely difficult, but also an urgent survival skill for decades (centuries?) of women who wanted to achieve economic stability and social success.

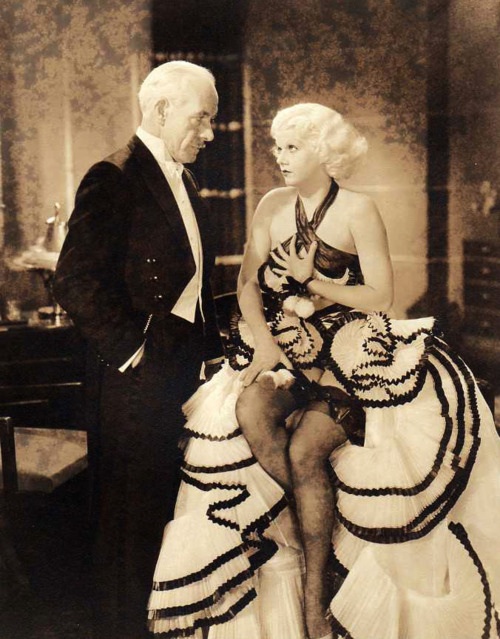

And boy, did Loretta Young ever work for it. Devout she may have been, but she wasn’t what you’d call sinless. At 17, and against the wishes of her strongly catholic mother, young Loretta ran off and married a much older co-star (Grant Withers). Not only did she brave the wrath of her family, she also received a fierce scolding from the family priest who told her that not only was she making a terrible choice personally, but that as a film actress, she had a serious responsibility to be a good role model for other young women. That’s some serious guilt. The marriage lasted less than a year. But Loretta wasn’t done sowing her oats just yet. In 1935, snowed in on the set of Call of the Wild, Loretta became pregnant by her very married costar, Clark Gable. Even if she’d wanted to, as a young catholic woman ending the pregancy wasn’t a comfortable option. But neither was having a baby out-of-wedlock, so with her mother’s help, Loretta managed not only to hide the pregnancy from the public and her very controlling employers, but to carry the baby to term. She then eventually staged an adoption of the infant girl, so she could raise the child without scandal. Whew! Talk about strength and determination. And consummate image management. So Loretta achieved her lady status the old-fashioned way. Through seriously hard work.

And she certainly knew something about the tensions between appearing ladylike while navigating the messiness of being fully human.

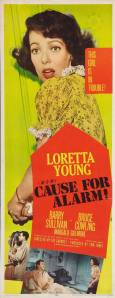

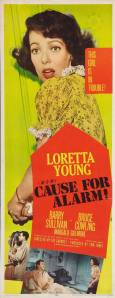

In honor of Loretta’s underrated acting chops and her undeservedly bland reputation, here’s a little tribute to one of her many excellent and sensitive performances, Cause for Alarm….A tight little noir that’s also a testament to the challenge of looking like a lady while being a person.

Cause for Alarm– The Unravelling of the Suburban Housewife

(If you haven’t seen Cause for Alarm, beware. There are plenty of spoilers ahead. Click the title below to view it on Youtube)

In aptly titled Cause for Alarm (1951), Loretta Young plays Ellen Jones, an ideal 1950s housewife. She’s lovely without being sexy, totally devoted to the needs of others and (almost) perfectly contented doing housework. In fact, she’s so perfectly smooth that, at first, she does seem like a dull character, as if care-taking and housekeeping are the jobs she was born to do. She’s the template for all the perfect wives soon to appear on the small screen–Donna Reed, June Cleaver and the rest. The appealing textures that a 30s and 40s dame might have brought to such a role aren’t here. There’s none of the tough-girl humor of Ann Sheridan or the seething ambition of a Bette Davis. Young is the consummate professional and she plays the role in a a style that’s as perfectly pressed as her flowered house-dress. Great posture, custard-voice, and utterly solicitous.

But there is anxiety. Ellen’s husband (Barry Sullivan) is very sick. He’s got serious heart trouble. So sick that he can’t get out of bed. And while he languishes upstairs, Éllen tidies the living room and worries. While pushing the vacuuming, her thoughts are expressed in voice-over. She’s tired and unhappy, “even housework seems like drudgery” when there’s no one to appreciate it. She scolds herself for being too selfish, for not being cheerful enough, for not thinking enough of his needs. She’s nurse, maid, and mother all wrapped into a tidy flowered package. And she worries it’s not enough.

But she’s right. It isn’t enough. Nothing will be enough for her invalid husband. He’s sick and getting sicker and, it’s twisting up his already troubled mind. He’s decided to blame Young for his illness, developing a paranoid fantasy that she and his doctor (an old friend of his, an old beau of hers) are having an affair and plotting to kill him. He’s written a letter to the district attorney, detailing the plot he imagines and Young has unwittingly mailed it for him. Once he knows it’s been mailed, he reveals his imaginings to her, then pulls out the gun he’s hidden beneath his pillow and threatens to kill her. She’s appropriately frightened and shocked, begging him to remember that she’d never hurt anyone, especially him. He can’t hear reason. But before he can shoot her, he crumples to the ground, anger and adrenaline bringing on a deadly heart attack.

This is where the movie, and Young’s performance, really rev up. Her husband is dead on the bedroom floor. There’s a gun in his hand and a letter saying that she was out to get him is on it’s way to the District Attorney. Completely unprepared for this kind of crisis, she does everything wrong. And all the whipped-smooth perfection of her house-wife persona dissolves in the heat of her panic. Frantic and desperate, but also keenly aware of the image she’s supposed to project, the tension between her abject panic and her serene but slipping persona is utterly compelling.

First things first. She’s got to get that letter back. Leaving the dead man on the floor, she rushes out of the house. Looking frantically for the postman, he’s nowhere to be seen. She searches her memory, which way did he say he was going? Making a guess, she takes off in a rapid clip. She’s really breaking the rules now! You’d never see June Cleaver running, sweating, racing down the block. She carelessly bumps into a well-dressed couple, and barely stops to apologize. They glare at her as she dashes away, the wife looks huffy, even shocked. Any other day, Ellen Jones would stop to smooth it over. But there’s no time. She rushes on.

When she finally finds the postman, he’s impossible. He wants to make small talk, complain about his tired feet, the heat. She tries desperately to be solicitous and polite, but her panic keeps breaking through. I’ve got to have that letter back. It wasn’t finished. I mailed it by accident. He rifles through his bag, finds it, but he is reluctant to hand it over. Please, my husband is very upset. He really wants the letter back. The impossible postman says hold on— I though you said you wrote it? I can’t give you someone else’s mail. Ugh. Ellen keeps stumbling. Changing her story. And the stubborn postman keeps holding that letter, just out of reach. She can’t take it anymore. She grabs for it, he jerks it back and it falls to the ground. She’s really overstepped her bounds now, getting shrill and grabbing for the letter. The postman’s had enough. He bends down for the letter, stuffs it back in his bag, and walks on.

She’s failed badly and she knows it. But she can’t afford to give up. Chasing after him, she tries another tack. Apologetic and sympathetic, she touches him, trying to soothe him- I’m sorry, I wasn’t thinking about your position….she’s even adds a touch of seduction, lowering her head, eyes big and soft. When she’s got his attention again, she plays the damsel. Soft-voiced and vulnerable, she reminds him that her husband is very sick and will be very upset if she doesn’t bring him that letter.

In this short tense scene, Young subtly and convincingly runs through all the approved 1950s approaches a woman might use to get what she wants— submissive politeness, flattery, helplessness and flirtation. And because she’s under so much pressure, we see the the verboten behaviors too—overt aggression, frustration, desperation, audacity. It’s an masterful, sympathetic performance.

Her new tactics don’t win her the letter, but they do get her a reprieve. The postman isn’t cruel, just a dull-witted rule-bound guy, a system guy. You run into them every day. So finally, he tells her look, why don’t you go down to headquarters and explain the situation to my supervisor. Maybe he can help.

It’s not what she wanted. But it is another chance. So okay. She’ll go down to postal headquarters. She races home to change.

Once home, she runs up the stairs but stops cold before opening the bedroom door—He is still in there. Here, the cinematography and setting work to underline her desperate position. Shot from below, Young is framed in the criss-crossing lines of the staircase railings- the orderly suburban home has become a threatening, unbalanced nightmare. And the sharp lines of the staircase railing remind us of the literal prison she’s desperate angling to avoid. Dead husband or not, she’s got to go into that bedroom.

She sidles in, carefully looking towards her closet and dressing table, and away from the dead man on the floor. The clock is ticking. She has to get to the post-office by 2:30 or the letter will be mailed. So she takes of her house-dress and sandals, hops into a little going-downtown day dress. She smooths her hair, plops on a hat and applies some lipstick to her lovely mouth, all the while giving herself a pep talk in voice over- you’ve got to stay calm, show them everything’s normal, act like any other housewife asking for a letter…. She stands up, smooths her dress, grabs her pocketbook and makes ready. On her way out, still carefully looking anywhere but the floor, she glances in the mirror over the wardrobe and there he is.

She has to do something to make things look better, at least to her, so she decides to remove the gun – hard to do from a clenched, dead hand. She has to force his fingers open and in the process the still cocked gun goes off. Bang. Her tidying up instincts aren’t helping her at all. Fortunately, when she peeps out the window, the only person who seems to have heard the gunshot is the cowboy-garbed neighbor boy, she yells down to him that it was just the radio. And being a lonely suburban kid immersed in his own imaginary world of six-shooters and indians, he takes her word for it.

Then, in her rush to see the postal supervisor on time, she pulls out of the driveway so carelessly that she almost runs down the neighbor boy on his trike. It’s a tight little movie. Every obstacle in her journey is the real stuff of suburban life. Nosy neighbors. Lonely children. Unwelcome relatives. Stolid postmen. Uncaring officials.

Cut to an establishing shot of the downtown post-office,an imposing stone building. Before she even enters, we know she’s in trouble. What can a fragile little housewife do in the face of an iceberg of authority like the postal system ( or the even more powerful legal system that’s threatening just over the horizon).

She does her best. Despite her obvious fear, she tries hard to play the concerned housewife. Smooth-voiced, ever-polite. And it starts to look like the official in gray suit he might give her the letter after all. But there’s a form to fill out. Her husband won’t have to come in, but he’ll have to sign it.

Seriously?! Passionately frustrated, Mrs. Jones does the kind of thing she’s probably never done before. She raises her voice. She gets almost shriek-y. She demands the letter. Her loss of control is her undoing. This stolid, gray-suited postal official won’t tolerate a hysterical, demanding woman.(You think of poor Betty Draper finally losing it and shooting the neighbors pigeons.) Emotions aren’t allowed. A woman like this negotiates the world through self-control and polite submission. Losing control is like taking off her girdle in public. So unbecoming. Additionally, the postal inspector has noticed that the letter is addressed to the district attorney. So, no dice, little woman. You just lost the game.

All the air goes out of the room. And out of Ellen. She’s been beaten. Her humanity got the best of her.

The energy of the movie totally depends on Young’s performance. She makes it rise and fall expertly. I didn’t quite believe, or relate to, or like, the confection-sweet housewife of her earlier scenes, but boy do I believe her undone housewife now. You’ve got to see the whole movie to appreciate the earnest sweetness of the early scenes.

The most poignant scene in the movie comes very near the end. As Ellen gets out of her car and walks zombie-like towards her front door, her next-door neighbor suddenly reaches out. She’s been there all day, a plain faced middle-aged woman in gardening gloves, alone in her front yard, trimming this, watering that, all the while eyeballing the curiously frantic exits and entrances of our heroine. Never saying a thing. But suddenly she stops quietly observing and speaks, “Mrs. Jones, I don’t mean to intrude….but I’ve been watching all day and I’ve had the feeling that you…that something was wrong. I know I haven’t been too neighborly…but…is there something I can do?” She means it. Her voice is warm, her eyes are sympathetic, her is posture open and inviting. But the camera tells the story. There’s defeated Ellen, alone by her front door, and in the next shot, there’s the kind neighbor, also alone, standing just behind a little white picket fence. The pretty, apparently civilized customs of middle-class life have kept them apart. And now it’s too late. Ellen’s voice-over is a gut-punchingly sad. As she puts the key in the lock, she thinks to herself wonderingly, “She could have been my friend….she could have helped me…”

Soon after going inside, her husband’s doctor, her old beau, stops by to check on his patient. She tries to send him away in order to protect him. He’s an old friend and he’s implicated too. She figures the police might show up anytime. But he won’t go and she ‘s too worn down to keep up an act. The dam bursts and she tells him everything. He tries to comfort her, but things are looking very bad.

Now, for my money, is one of the best ironic endings of all time. Here’s Ellen, back at home, hopeless and numb. In one day, her whole life’s been demolished. And the doorbell rings.

It’s the postman. He’s bringing the letter back to her after all. Not because he or his supervisor decided to have a heart. Nope. For the completely opposite reason. Insufficient postage. The postman feels awkward about the whole thing, so he rattles on about postal regulations, officiously explaining why sufficient postage is necessary and how he should have noticed how thick the letter was. Then he complains about his own small irony—not enough postage and I have to deliver it twice. Crazy business.

When the postman leaves and she closes the door, she clasps the letter bewildered. The system was going to thoughtlessly destroy her, but in the end, it just as heartlessly reprieves her. Because it doesn’t care about her at all. It only cares about itself, its rules. It’s a mundane kind of horrible. Like a Kafka story. This is the best we can hope for. That the system that grinds us will choke and spit us out.

Young plays this last scene beautifully. The crazy-making tension of the day, the ridiculous but deadly bureaucracy, then a sudden last second reprieve for no human reason. She laughs and cries simultaneously. Then sits herself forlornly in the rocking chair.

Now she’s in the hands of the dull but honorable doctor who’s loved her all along. But there’s no clinch. No Hollywood comfort. They just sit together and watch the letter burn